How Great Powers Avoid War: Lessons from the Concert Model

Discover how an informal, balance-of-power system (adapted for today’s multipolar world) can prevent conflict, manage rivalries, and restore stability.

The Balance of Power as a Mechanism of Peace

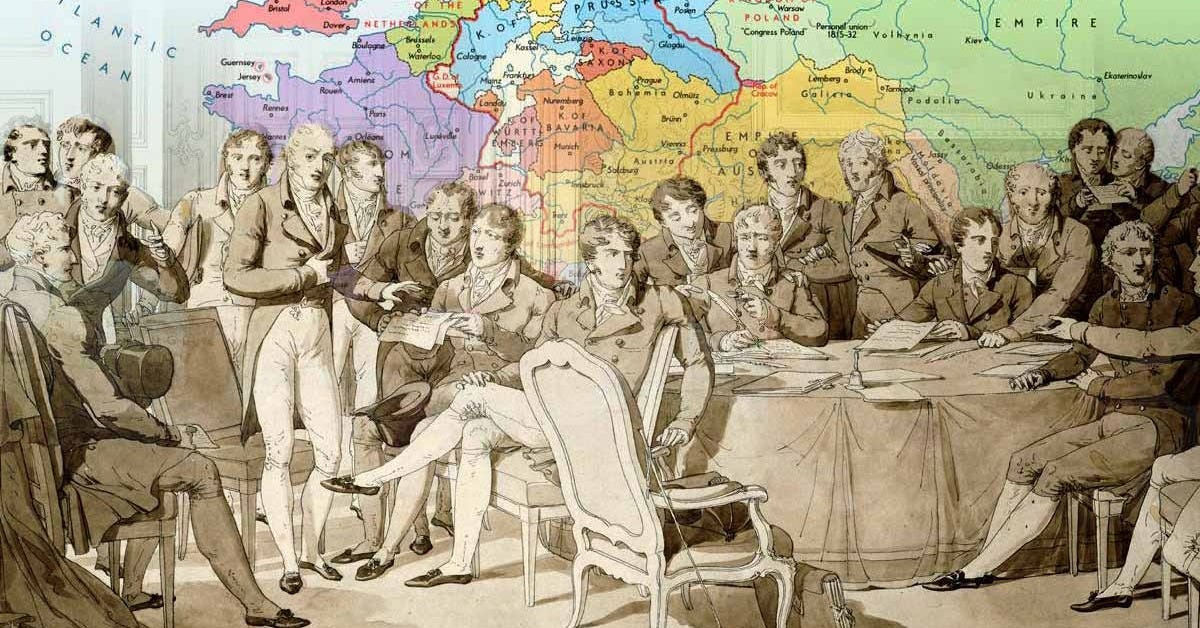

The Concert of Europe arose in the aftermath of a continent ravaged by revolutionary upheaval and imperial conquest. The Napoleonic Wars had not simply disrupted European politics; they had obliterated the previous framework of dynastic legitimacy and multipolar equilibrium. In response, the victors of 1815 (Austria, Prussia, Russia, Great Britain, and later a reintegrated France) undertook a recalibration of the international system based not on shared ideology or treaty law, but on a pragmatic balance of power designed to prevent future continental-scale warfare.

The Vienna settlement that followed Napoleon's defeat did not codify a universal legal regime nor attempt to impose a supranational authority. Instead, it recognized the anarchic nature of international politics and responded with an informal, elite-driven mechanism for managing instability. The great powers engaged in recurring, closed-door diplomatic consultations to monitor shifts in the distribution of capabilities, and to intervene, collectively or individually, if a state sought to revise the status quo through force.

Critically, this arrangement was exclusionary by design. Only those states with the military strenght and geopolitical reach to shape outcomes were admitted. Legitimacy within the Concert did not refer to adherence to law or principle; it signified material capability to influence the balance of power. Order was upheld not through treaties or institutional enforcement but through anticipatory behavior: states adjusted policies to avoid triggering coordinated responses from their peers. Peace, in this configuration, was maintained not by goodwill but by strategic calculation.

Domestic Upheaval Erodes International Consensus

The long peace fostered by the Concert masked an accumulating tension within the system. While effective at managing relations among states, the Concert was increasingly vulnerable to challenges arising from within those states. Its ideological foundations, centered on dynastic legitimacy and monarchical continuity, became misaligned with the profound social and political transformations unfolding across 19th-century Europe.

Industrialization altered the material structure of societies, expanding urban populations and accelerating the spread of literacy and political consciousness. Nationalist and liberal movements emerged, demanding constitutional rule, representative institutions, and national self-determination. These movements were the expression of structural forces reshaping the relationship between rulers and ruled.

The revolutions of 1848 represented a critical stress test. Across the continent, entrenched regimes were challenged by popular uprisings. The response of the Concert powers was initially uniform: suppression. However, the scale and persistence of unrest made it clear that military intervention alone could not reverse the underlying trends. Britain's refusal to participate in interventions, citing both strategic detachment and domestic liberal sentiment, marked the beginning of the Concert’s fragmentatoin.

The contradiction became inescapable. A system designed to preserve external stability could not indefinitely suppress internal change. As nationalism reshaped political legitimacy and liberalism transformed governance, the consensus underpinning the Concert frayed. Its coherence, always dependent on the internal stability of its members, eroded in the face of this new political geography.

Shared Foundations Made Informal Order Work

The operational success of the Concert of Europe cannot be divorced from the specific structural conditions of 19th-century Europe. It functioned within a confined geographic arena, where the major powers shared a broadly similar cultural, political, and strategic worldview. These powers were governed by monarchies, staffed by aristocratic elites, and steeped in a tradition of diplomacy rooted in personal ties and shared norms.

Geographic proximity allowed for rapid communication, face-to-face negotiation, and a common understanding of regional threats. The absence of deeply divergent civilizational paradigms reduced interpretive friction. Even where interests diverged, the language and logic of diplomacy remained mutually intelligible. Moreover, empire, not universal ideology, was the common mode of power projection. Strategic goals were regional, and while competition was fierce, it was bounded.

By contrast, the contemporary international system is vast, heterogeneous, and deeply interconnected. Today’s major powers operate across disparate regions, with contrasting historical experiences, political systems, and strategic cultures. The conceptual core of terms such as “sovereignty,” “intervention,” or “order” varies significantly between capitals, from Washington to Beijing, Moscow to New Delhi.

This diversity introduces profound constraints on replicating the Concert model. What was once a relatively coherent club of imperial monarchies is now a fractious array of states, each embedded in overlapping systems and pursuing divergent objectives. The lesson, therefore, is not to reproduce the form of the Concert but to adapt its functional logic: a limited, flexible mechanism for interest-driven coordination among system-shaping powres.

Informal Diplomacy Outperforms Rigid Institutions

In the aftermath of World War II, a new architecture of global governance was constructed, centered on legalistic institutions like the United Nations and Bretton Woods system. This order, while stabilizing for decades, has come under growing strain. The diffusion of power, paralysis of formal bodies like the UN Security Council, and return of strategic rivalry among major powers have revealed the limits of institutionalism.

A 21st-century Concert would not replace these institutions nor attempt to legislate international norms. It would serve instead as a

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Horizon Geopolitics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.